Image credit: Unsplash

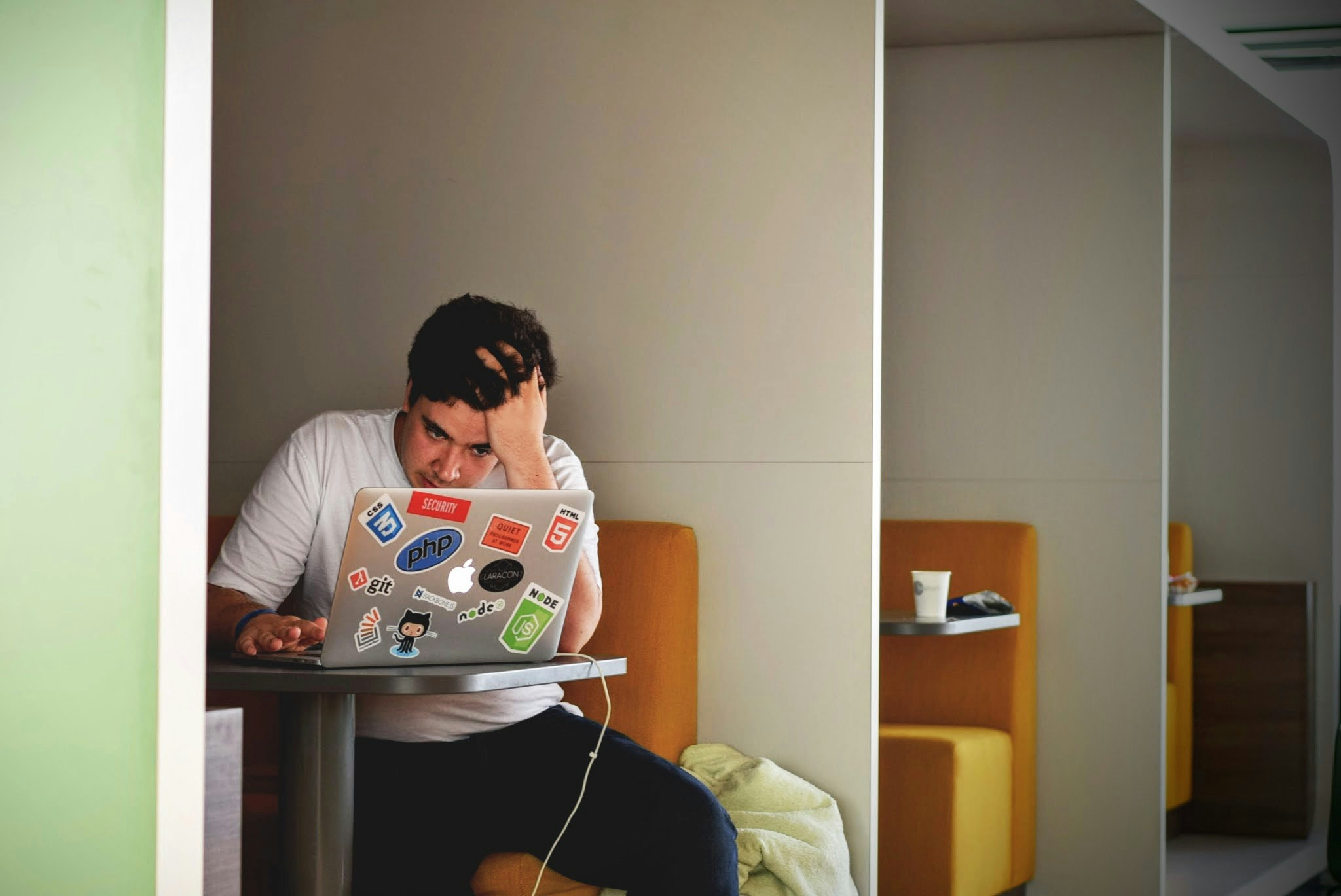

An employee working at Fisker Inc. reported that the most pressing concern inside the EV startup was not if its Ocean SUV would get built. Instead, this employee claimed that their peers were worried about Fisker’s ability to handle the problems that arise after a company puts a car on the road. They were focused on building the car, not the company.

Fisker founder and CEO Henrik Fisker originally had an automotive startup fail a decade ago, possibly for this reason. That company, which was called Fisker Automotive, was able to get a hybrid sports car into the hands of several thousand customers. However, the company buckled after it faced complaints about quality, the failure of its battery supplier, and even a hurricane that sunk a ship full of vehicles.

The employee’s warning that the new Fisker was headed down a similar path could be seen as foresight. Fisker filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in mid-June after only one year of shipping its SUV to customers around the world. This undoing is, in many ways, tied to its inability to address the worries the aforementioned employee raised in 2022.

The employee wasn’t alone. Dozens of others who worked at Fisker have voiced these concerns since, with almost all of them on the condition of anonymity. These conversations not only informed stories about the Ocean SUV’s quality and service problems but also Fisker’s internal chaos and decisions from Henrik Fisker and his co-founder, wife, CFO, and COO Geeta Gupta-Fisker. Most of the employees reported that the lack of preparedness had run deep and that it permeated almost every division of the company.

The software that powered the Ocean SUV was ultimately underdeveloped and contributed to the delay of its launch to the point where it resulted in problems that Fisker had to troubleshoot in May 2023. A similar event happened when the company made its first deliveries in the United States in June 2023, when one of its board members’ SUVs lost power shortly after taking delivery.

Fisker shipped far fewer Ocean SUVs than they originally projected. Even after the company lowered sales targets for 2023, it still struggled to hit its internal sales goals. Sales employees have stated that they were calling potential customers repeatedly in the hopes of selling vehicles because few leads were coming in, and others in different departments ended up pitching in to sell cars as well.

Many customers who did receive their Ocean SUVs ran into problems. These included sudden power losses, trouble with braking systems, problematic door handles that would temporarily lock people in and out of the vehicles, as well as glitchy key fobs and buggy software. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration has since opened four investigations into the Ocean SUV.

Fisker has struggled with the quality of its suppliers, and employees have stated it did not build out a buffer of spare parts to compensate for potential problems. This placed pressure on the people in charge of fixing the cars as they ran into issues and led to the company pilfering parts from not just Magna’s production line in Austria but even from Henry Fisker’s own car (though Fisker has denied these claims).

Meanwhile, lower and mid-level employees went to great lengths to support a slow-growing customer base. One owner stated that an employee took a phone call on a personal cell phone while at a funeral, while others have reported doing company business while in hospital. One hourly employee even filed a prospective class action suit over the long days, nights, and weekends many worked.

The company has admitted that it did not have enough staff to handle customer service requests. Workers from other departments pitched in to assist with these problems, while some are still fielding customer calls despite having left Fisker weeks or even months ago.

Fisker has struggled for a while. At one point, due to internal accounting practices, it lost track of around $16 million in customer payments. It also suffered multiple delays in required reporting to the Securities and Exchange Commission. One of those delays allowed one of the company’s lenders to eventually take over in the final months.

Despite these problems, Fisker is continuing to express that its speed to market is an accomplishment even as the bankruptcy process begins. In a press release about the Chapter 11 filing, a nameless spokesperson stated that “Fisker has made incredible progress since our founding, bringing the Ocean SUV to market twice as fast as expected in the auto industry.”

The representative went on to state that Fisker “faced various market and macroeconomic headwinds that have impacted our ability to operate efficiently.” While this is true in some respects, there is no introspection about the multiple issues that led to the company’s number of problems. Those issues may surface in the Chapter 11 proceedings, during which the company aims to settle debts owed between $100 million and $500 million or even to restructure assets totaling between $500 and $1 billion.

Magna has since stopped producing the Ocean SUV and expects a $400 million revenue loss this year. It is unclear how much progress Fisker made on its future products, the sub-$30,000 Pear EV and the Alaska pickup. The engineering firm that helped co-develop those vehicles has recently sued Fisker, calling the projects and their likelihood of development into question.

Fisker has stated in a press release that it will continue “reduced operations,” which include “preserving customer programs and compensating needed vendors on a go-forward basis.” Ultimately, they will continue to manage operations until there is a willing buyer.

The bankrupt Fisker Automotive did find a buyer a decade ago and ultimately morphed into a startup called Karma Automotive, which still exists today. Three other EV startups that recently filed for bankruptcy—Lordstown Motors, Arrival, and Electric Last Mile Solutions—were able to sell off their assets to peer companies in the space.